When the Light Fades, Our Genes Speak Differently — Understanding the Winter Blues

Every fall, as daylight hours shrink and the cold settles in, many of us feel our energy dip, our motivation fade, and our sleep change. We call it the “winter blues” — or, in its stronger form, Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

But why do some people experience these shifts more intensely than others?

Part of the answer lies in our genes.

Light, Serotonin and Genetics — The Trio Behind Our Mood

Sunlight is key to producing serotonin, the neurotransmitter often called “the happiness molecule.”

Our ability to regulate serotonin, however, depends partly on a gene called SLC6A4, which codes for the serotonin transporter (5-HTT).

Certain variants of this gene make some people more sensitive to seasonal light changes: as days grow shorter, serotonin reuptake becomes less efficient — leading to lower mood and energy.

In other words, it’s not “just in your head.” It’s also in your biology.

Studies from Oxford University and the University of Toronto have shown that people carrying specific versions of SLC6A4 report more pronounced seasonal mood changes — especially in northern regions like Canada.

The Role of Vitamin D — and the VDR and GC Genes

Light doesn’t only affect serotonin; it also drives the production of vitamin D, the so-called “sunshine vitamin.”

When our skin absorbs UVB rays, it synthesizes vitamin D — essential for regulating hundreds of genes in the brain and immune system.

But our genetic makeup influences how effectively vitamin D does its job.

Two genes in particular, VDR (vitamin D receptor) and GC (vitamin D-binding protein), determine how the vitamin circulates and functions.

In some people, a less active VDR receptor may reduce vitamin D’s effects on serotonin synthesis — making them more prone to winter mood dips.

That’s why two people living under the same gray sky can react so differently to the season: their genes shape how their bodies “read” the light.

Epigenetics — When the Environment Talks to Our DNA

Winter doesn’t alter our DNA, but it changes how our genes express themselves — a field known as epigenetics.

Stress, reduced daylight, sleep disruption and diet can all modify the activity of genes involved in neurotransmission and circadian rhythm, such as CLOCK and PER3.

The good news? Epigenetics is reversible.

Our habits, routines and environment can “re-activate” beneficial pathways.

That’s why simple changes — light exposure, exercise, balanced nutrition — truly have biological impact.

Supporting Your Winter Balance

1. Seek the light

Just 15–20 minutes of midday sunlight can stimulate serotonin and vitamin D production.

Light therapy lamps (10,000 lux) are also clinically proven to help with SAD symptoms.

2. Move your body

Exercise activates the same brain circuits as light exposure. It boosts BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor) — a key gene-protein supporting neuronal growth and emotional balance.

3. Eat for your mood

Foods rich in tryptophan (bananas, eggs, nuts, salmon) support serotonin synthesis. Omega-3s, vitamin D and magnesium also help regulate mood and stress.

4. Know your biology

Wellness DNA tests, such as those offered by Adnà, can analyze genes like SLC6A4, VDR, and CLOCK.

Understanding your genetic tendencies helps tailor your lifestyle — from light exposure and nutrition to sleep and supplementation.

In Conclusion

Our emotions are not dictated by the weather alone — they reflect a delicate dialogue between light, hormones, and our genetic makeup.

Acknowledging this interaction allows us to act with intention — choosing the right light, the right habits, and even the right insights into our DNA.

This winter, instead of resisting the darkness, what if we learned to understand it?

After all, your DNA has answers.

Scientific References

- Praschak-Rieder N. et al. (2007). Seasonal variation in human brain serotonin transporter binding. Archives of General Psychiatry.

- Kerr J. et al. (2022). SLC6A4 polymorphisms and vulnerability to seasonal affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders.

- Holick M.F. (2017). Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine.

- Eyles D.W. et al. (2013). The vitamin D receptor and the regulation of serotonin synthesis. FASEB Journal.

- Lam R.W. et al. (2016). Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder: efficacy and mechanism. CNS Drugs.

- Ciarleglio C.M. et al. (2008). CLOCK gene variants and circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep.

I was very impressed with the quantity and quality of the results. The test is easy to do and the return process is well managed. I highly recommend this Quebec-based company.

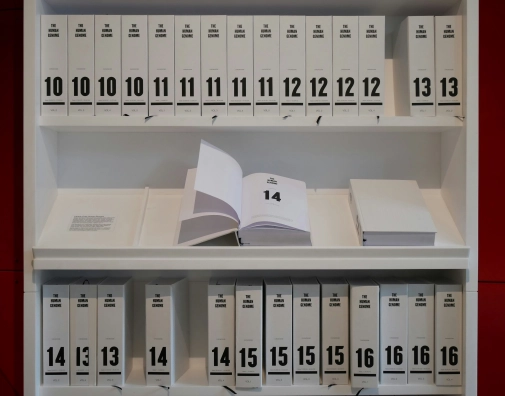

Other Journal : Files

VIEW MORE